In the last two posts I described tools to validate the required intermediate SSL certificate chain for a given server certificate, and to validate that the private key and server certificate are a match. Once the SSL configuration is deployed though, how do we check that everything is working correctly and the new certificate is in place?

Checking deployed SSL Certificates and Intermediates

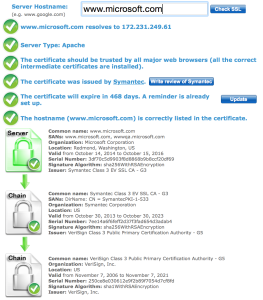

The simple answer is “use one of the tools already out there on the Internet.” That’s a fair answer, and I have been known to use some of these. A quick Google search shows a validator on SSLShopper:

There’s also a similar tool on DigiCert:

These are great tools and I strongly encourage using them to check your sites. However, there’s one situation where they can’t help you, and that’s when your site is only accessible internally. How do I do certificate validation for private sites?

OpenSSL To The Rescue. Again

Yet again, OpenSSL is my tool of choice because not only can it open an SSL connection to a VIP, but it can also show the certificates it is sent. You may be thinking “Why not just use a web browser?” Again, a fair question, but as I mentioned in my post “When SSL Certificates Go Wild,” the problem with web browsers is that they are too helpful. They don’t tell you if the certificates are delivered in a non-optimal order, they don’t tell you if you are sent certificates you don’t need, and they also cover up a missing intermediate certificate by automatically downloading that issuer certificate based on the Authority Information Access fields in the server certificate (which is effective but slows down communication).

Operational Annoyance

OpenSSL tells you what you got sent by the server; no more, no less, and that’s perfect for what we need. The basic command format is simple:

openssl s_client -showcerts -connect mysite.com:443

The output to this command displays the certificates sent, and OpenSSL validates each certificate in the chain as well. The problem, as always, is to remember the syntax and knowing how to interpret the output. If I want to know the expiration date of the server certificate (useful when you just updated a certificate and want to know if it’s being served correctly), well that information is not directly in the command output. It would be necessary to grab the certificate text from the command output and then feed it into openssl x509 -noout -text which would decode it. Who wants to do that all the time? Not me.

Operational Solutions

I’ve written another perl tool in the same vein as checkcert and checkkey, which wraps the OpenSSL command to validate the certificate chain and present the output in a clear fashion. While we’re there, why not grab the expiration date too?

Scripty Magic

Since this is yet another ‘quick and dirty’ script born of laziness, I find myself once more using Perl to do my dirty work, in turn calling openssl to do the truly difficult stuff. The script is called “checkssl.”

checkssl

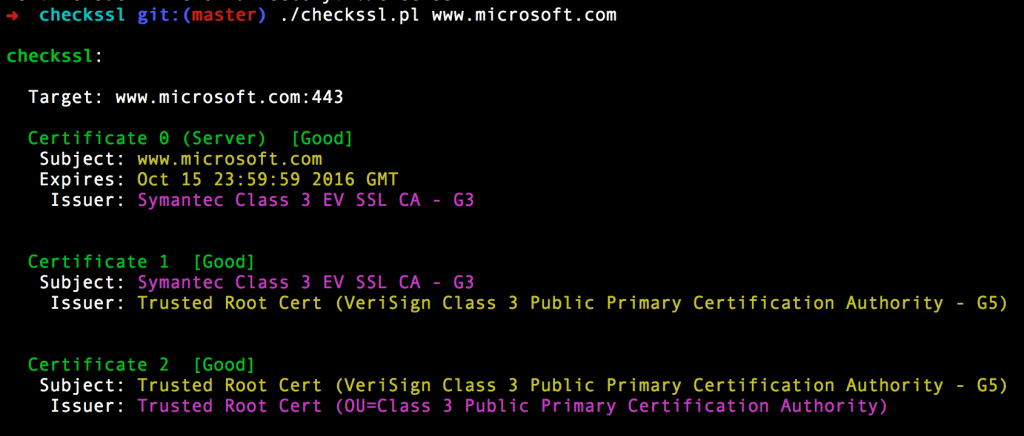

Give checkssl an IP or hostname and it will go check the site for you:

The colors in the output match the issuer of one certificate with the subject of the next level up in the chain, and note that the server certificate (the first cert) has its expiry date listed for convenience.

Rather than simply reformat the output from openssl, the script notes errors on any level of certificate and will display them. It also does its own validation of the order in which certificates were received, and compares them to the order they should be in, and will warn you if the certificates are out of order. Most browsers won’t care if this is the case, but every now and again some lame SSL implementation will fail if they’re not. The script also identifies certificates sent to the client that are not in the chain. Yes, that does happen!

SNI

Developing this script also reminded me about SNI (Server Name Indication), which I had forgotten about, but is necessary to connect to some sites. In a normal SSL connection, encryption is negotiated prior to the client requesting a site and path. The server certificate has to be sent before the client says which server it wants to connect to, and that’s why traditionally it’s only possible to have one SSL site hosted on each IP.

SNI is an extension to TLS that allows the client to specify the hostname of the site it wants to connect to, as part of the initial negotiation. That information allows the web server (or any device proxying the SSL connection on the server’s behalf) to switch in the correct certificate for that site when setting up the TLS connection. That way you can have unlimited SSL sites running on a single IP. I would posit that most sites do not use this, because not every client supports it, but some most certainly do, and to connect to those sites requires an additional openssl option to be set.

SNI Support – Type 1

The checkssl script will try to connect without SNI at first. If that fails, the script will automatically try again using SNI, sending the command argument as the hostname:

➜ checkssl git:(master) ./checkssl.pl www.somesite.com

Initial connect failed. Trying again with SNI...

checkssl:

Target: www.somesite.com:443 (requires SNI)

[...]

SNI Support – Type 2

In the event that checkssl is called with an IP address rather than a hostname, a second argument can be given, which is the FQDN to be used in SNI, e.g.

checkssl 1.2.3.4 www.microsoft.com

Think Lazy™

This script is arguably more of a time saver than the previous scripts, in as much as it is pulling together multiple commands and doing an additional level of analysis that is not included in the underlying tools by default. It solves a problem for internal websites, and some testing on a number of sites has revealed some fascinating behavior that would not otherwise have been noticed. Can’t argue with that.

GitHub

Yes, but I need some time to sanitize it first. Hang in there; your laughter can wait a little.

“Perl to do my dirty work” – priceless.

Looking forward to see your code.

Cheers!