Last month I visited Interop NYC 2014 as a guest of Tech Field Day Extra! where our group was given a presentation about the new Cisco ISR routers by Matt Bolick, a Technical Marketing Engineer for Cisco.

The Integrated Service Routers (ISRs) themselves seem pretty feature packed, covering four key areas:

- Transport independence (DMVPN)

- Intelligent Path Control (PfR v3)

- Application Optimization (WAN optimization, ADC and WAAS)

- Secure Connectivity (Scalable, strong encryption, IPS, web filtering, etc.)

Rather than reinvent the wheel, Matt explained that the idea was to use existing protocols in a useful new way; in this case in particular to offer secure hybrid transport across MPLS and Internet for private cloud and DC access, probably ultimately moving to just Internet connectivity base on the shift Cisco has seen in how corporations see their branch offices (and specifically how much they want to reduce costs!).

So far so cool, but I figure you can look up all the specifications and features for yourselves so I won’t bore you with much more of that here. There was something else that tickled me though.

ISR Performance Figures

The new routers have some interesting performance claims:

- 4321 = 50–100 Mbps

- 4331 = 100–300 Mbps

- 4351 = 200–400 Mbps

- 4431 = 500–1000 Mbps

It’s not often you see such widely varying throughput figures. Perhaps you might assume that the lower figure applies when you have enabled lots of features, and the higher figure applies when nothing is enabled (the classic “ideal conditions” performance test that network manufacturers prefer to use). It turns out that this is not the case.

CPU Cores

Licensing on the ISRs is based on throughput. If you license the full throughput you’ll get the bigger performance figure, and if you don’t, you’ll get the smaller figure. This is implemented internally by reducing the number of CPU cores that are actively processing the data. When you license “more throughput”, those unused cores magically get enabled and throughput goes up.

So you might think then that a low-end licensed ISR 4321 (50Mbps) must just have awful throughput when things like compression and encryption are enabled. Again, not so.

Shapers

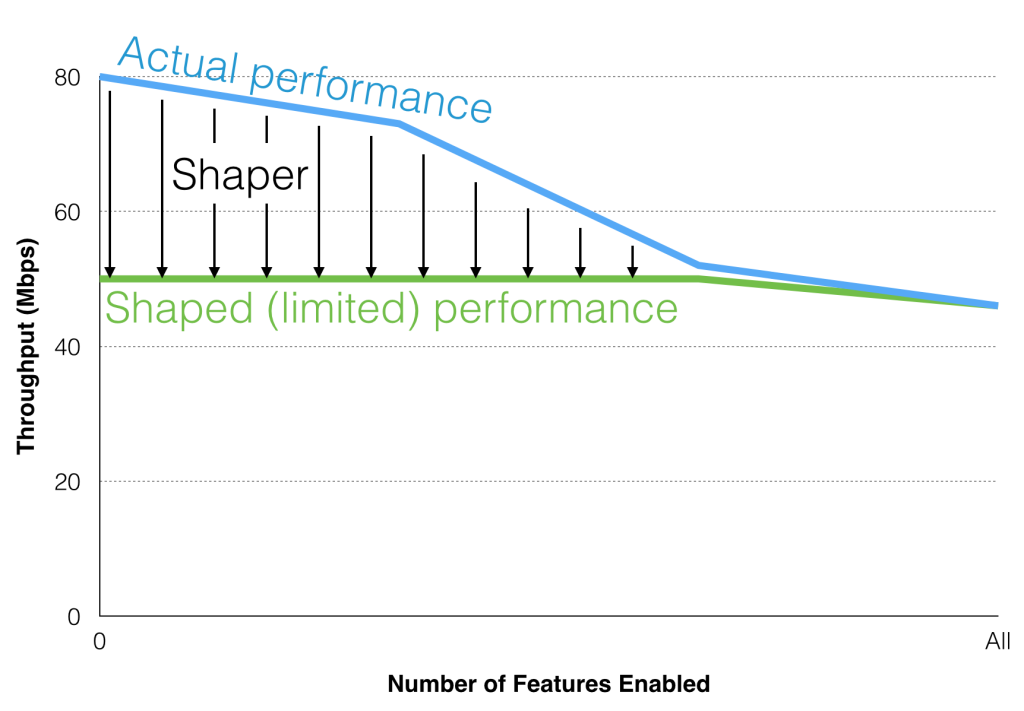

The ISR has an internal shaper that effectively limits throughput. Yes, limits it. Not for licensing purposes, but actually to ensure that performance doesn’t appear to suffer when features are enabled. When we were told that it was possible to enable all the features without a performance hit, we were understandably cynical, but it makes sense if you consider the idea that that ISR’s “ideal world”performance is in fact higher than the performance figures suggest. Let me explain with a diagram:

Even though the enabled CPUs are capable of more than 50Mbps when they’re not stressed by additional features, an internal shaper limits the throughput to 50Mbps. Why? Because that allows performance to remain consistent at around 50Mbps even when all the features are enabled. That’s a refreshing approach in many ways; we’ve all been bitten I’ll bet by paper performance figures that turn to dust when you start loading up a device and enabling features. From a marketing perspective it’s a risk because it may show a lower quoted performance than competing platforms, but I think it will pay off when it’s understood that this seems to be a reliable figure in all situations. I wonder if we can see firewall manufacturers taking the same approach?

Even though the enabled CPUs are capable of more than 50Mbps when they’re not stressed by additional features, an internal shaper limits the throughput to 50Mbps. Why? Because that allows performance to remain consistent at around 50Mbps even when all the features are enabled. That’s a refreshing approach in many ways; we’ve all been bitten I’ll bet by paper performance figures that turn to dust when you start loading up a device and enabling features. From a marketing perspective it’s a risk because it may show a lower quoted performance than competing platforms, but I think it will pay off when it’s understood that this seems to be a reliable figure in all situations. I wonder if we can see firewall manufacturers taking the same approach?

The Videos

Don’t miss the videos of the presentation. It’s packed with information and is a great introduction to this new generation of ISRs. Plus you’ll have a chance to see what triggered this comment:

“Even if you turn off CEF on a modern IOS router, it’s really still doing CEF under the hood.”

Cisco ISR 4400 Series Introduction from Stephen Foskett on Vimeo.

Cisco ISR 4400 Series Architecture from Stephen Foskett on Vimeo.

Cisco Intelligent WAN Introduction and Overview from Stephen Foskett on Vimeo.

30 Blogs in 30 Days

This post is part of my participation in Etherealmind’s 30 Blogs in 30 Days challenge.

Disclosures

I attended Interop as a delegate at the invitation of Gestalt IT, who ran this Tech Field Day Extra! event. The events are funded by the sponsoring vendors who “buy” time to talk to the delegates, and that money in turn funds my travel, accommodation and food while I am there. I am not paid to attend this event (I take vacation from work and do it on my own time), and I am not obliged to blog, tweet, or otherwise publicize any sponsor of the event. Further, when I do choose to publish content related to the event, I do so at my own discretion, and the content and opinions expressed are mine alone without any interference from any other parties.

Please see my general disclosures page for more information.

These look like a great new product from Cisco, and I hope they live up to what they say they can achieve, I am about to roll them out for my company for a DMVPN/ iWan piolet in APAC.

While I like the idea of knowing the base performance I’ll see with all features turned on, if you’re not super feature rich, you might see more performance out of an isr2 because the overall throughout isn’t shaped.

This doesn’t seem to be called out anywhere and people should be aware that while the min throughout is well known, so is the max, and it’s less than you will see out of an isr2 routing large packets in many common configurations.

Hi,

I’m trying to find out if AX license includes both Security and Data licenses as well and we can run routing protocols like BGP/OSPF/EIGRP with the AX license. Cisco site says so but I’m looking for detail features of AX which should mention routing protocols as well.

Can anyone please help?

Bad strategy from Cisco – why would I go for a lower throughput, clamped down router if the ISRG2 can perform better in my use case?

In my environment (and I suspect many others might relate to this), I have only NAT, ZBFW and a few IPSEC tunnels turned on, and I can easily achieve 200Mbps with a 1900 series.

Pfft! That’s pretty funny. Not even close to realistic unless you’re talking one or two connections behind a 1941. Even then it depends on the apps/protocols that just happen to be in use at the time. LMAO!